The delicate art of antique gold restoration walks a fine line between preservation and alteration, raising profound ethical questions about how much intervention is too much. At the heart of this debate lies the concept of patina—the accumulated wear, tarnish, and subtle discolorations that whisper an object's history through its very surface. For conservators, collectors, and cultural institutions, deciding whether to remove or retain these visible layers of time often feels less like science and more like philosophy.

Patina as historical fingerprint has long been considered the visual archive of an artifact's journey. The faint oxidation patterns on a 17th-century snuffbox might reveal its origins in Dutch colonial trade routes, while the uneven wear along a Byzantine reliquary's edges could testify to centuries of devotional handling. "When we erase these traces," notes Dr. Eleanor Voss of the International Conservation Institute, "we're not just cleaning metal—we're editing out chapters from a material biography that can never be rewritten." This perspective has gained particular traction among European museums, where a 2018 survey revealed 73% of major institutions now mandate patina preservation in their conservation guidelines.

Yet the pro-restoration camp presents compelling counterarguments. Many private collectors and auction houses contend that historical grime often obscures an object's true craftsmanship. The controversial 2019 cleaning of the Rothschild Fabergé Egg—which revealed previously invisible guilloché enamelwork beneath two centuries of oxidation—sparked heated debate when its auction price nearly tripled post-restoration. "We're not destroying history," argues Geneva-based conservator Marc Laurent, "we're removing the visual static that prevents modern eyes from appreciating these objects as their creators intended."

The ethical calculus grows even more complex when considering culturally significant artifacts. The 2021 restoration of a pre-Columbian funerary mask prompted outrage from descendant communities when conservators removed what Western scientists called "corrosion," but Indigenous elders recognized as ceremonial libation residues. Such incidents have spurred organizations like UNESCO to develop nuanced protocols distinguishing between "degradative patina" (harmful chemical changes) and "historical patina" (meaningful surface evidence).

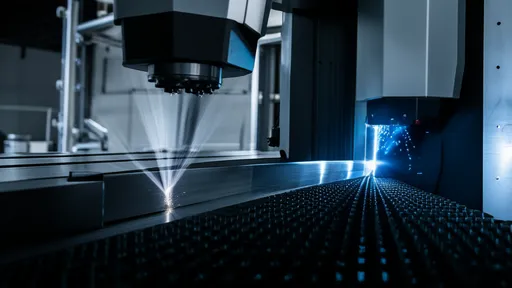

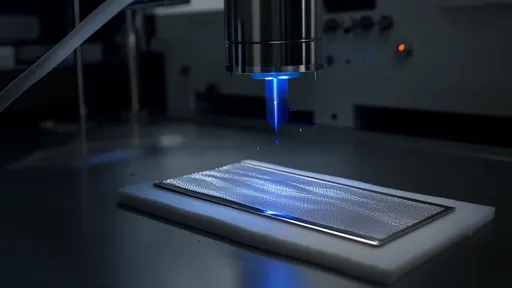

Technological advancements further complicate these decisions. Modern laser cleaning systems can now target specific molecular compounds, theoretically allowing conservators to remove copper sulfides while preserving mercury gilding. But as the Metropolitan Museum's 2022 symposium revealed, even this precision raises questions: should we value all original materials equally, or prioritize those with historical narratives? The museum's controversial decision to preserve nicotine stains on a 1920s cigarette case (evidence of its original owner's habits) while removing tarnish divided the conservation community.

Perhaps the most fascinating development comes from digital reconstruction techniques. Institutions like the British Museum now employ 3D modeling to create "patina maps" before treatment, allowing virtual restoration experiments. This technology enabled curators to determine that a Saxon arm ring's blackened areas weren't medieval wear, but rather 19th-century silver polish residue—information that radically altered conservation approaches. Such case studies suggest future ethics may hinge less on "to clean or not to clean" than on developing sophisticated diagnostic tools to read patina's hidden stories.

The market's influence cannot be ignored in these discussions. While major museums increasingly favor minimal intervention, private collectors often demand restored brilliance—a tension starkly visible in the 2023 controversy over a Renaissance pendant whose cleaned version fetched €2.4 million at auction, despite protests from the original exhibiting museum. This commercial pressure has led some conservators to adopt compromise techniques like "partial patina retention," where select areas remain untouched as historical reference points.

Legal frameworks struggle to keep pace with these nuances. The 1954 Hague Convention protects cultural property during conflict, but offers little guidance on microscopic surface alterations. Italy's stringent cultural heritage laws contrast sharply with more permissive U.S. regulations, creating conservation gray zones when objects cross borders. The recent ICOM-CC guidelines attempt to bridge these gaps by introducing the concept of "ethical reversibility"—any treatment should allow future conservators to distinguish original surfaces from modern interventions.

Emerging scholarship suggests we may be asking the wrong questions altogether. Dr. Yasmine al-Hadidi's groundbreaking work at Cambridge posits that patina itself evolves meaning—the oxidation we see today differs chemically from what medieval artisans would have recognized as natural aging. This challenges the very notion of "original" surface conditions, implying our conservation ethics might reflect contemporary aesthetic values more than historical truth.

As the field grapples with these dilemmas, one consensus emerges: each treatment decision requires case-specific deliberation weighing artistic intent, material science, cultural context, and future study needs. The golden mean—quite literally—may lie in developing conservation approaches that neither fetishize grime nor erase history's fingerprints, but rather cultivate the wisdom to read between the layers.

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025