The ancient art of lost-wax casting, a meticulous process that transforms raw materials into intricate metal sculptures, remains one of the most fascinating techniques in metalworking. From the initial wax carving to the final polishing touches, each step demands precision, patience, and a deep understanding of materials. This method, also known as investment casting, has been refined over centuries, yet its core principles remain unchanged. The journey from concept to finished piece is a dance between craftsmanship and chemistry, where even the smallest misstep can alter the final result.

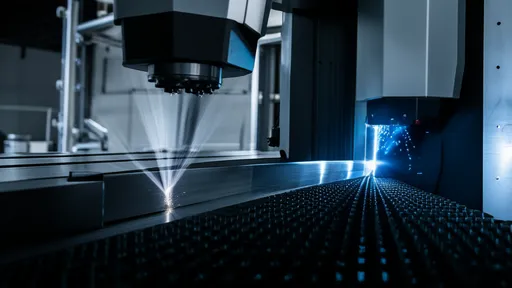

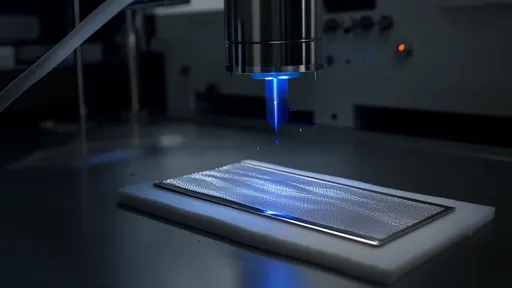

Creating the wax model is where the artist's vision first takes tangible form. Skilled artisans carve or sculpt the design in wax, a material chosen for its malleability and ability to hold fine detail. The wax model must account for metal shrinkage during casting, requiring the artist to work with mathematical precision. Some workshops use 3D printing for complex designs, but traditional hand-carving remains prized for its organic quality. This stage often consumes the most time, as every imperfection in the wax will translate to the final metal piece.

Once the wax model achieves perfection, the spruing system is attached. These wax rods create channels for molten metal to flow and gases to escape during casting. The arrangement is both an art and science - too few sprues may cause incomplete casting, while too many leave excessive cleanup work. Experienced founders develop an intuition for optimal sprue placement, considering factors like metal viscosity and the piece's weight distribution. The sprued model then undergoes multiple ceramic coating layers to form the mold.

The investment process involves dipping the wax assembly into liquid ceramic slurry, then coating it with fine silica sand. This step repeats until achieving sufficient thickness to withstand molten metal's tremendous heat and pressure. Between coatings, each layer must dry completely - a process that can take days for large pieces. The ceramic shell grows progressively coarser with outer layers, creating a composite structure that balances strength and permeability. This painstaking buildup transforms the delicate wax model into a robust negative mold.

With the ceramic shell complete, the dewaxing phase begins. The mold is inverted and placed in a high-temperature kiln, where the wax melts and drains out through designed channels - hence the term "lost-wax" casting. What remains is a hollow ceramic cavity precisely mirroring the original wax model. The kiln firing also cures the ceramic, making it strong enough to handle molten metal. Temperature control during this phase is critical; too rapid heating can crack the mold, while insufficient heat leaves residue that compromises casting quality.

Metal preparation and pouring occurs simultaneously with dewaxing. The chosen alloy - whether bronze, silver, or gold - is melted in a crucible reaching temperatures between 1,000°C to 1,200°C. Founders monitor the metal's viscosity and temperature with practiced eyes, knowing the exact moment to pour. The liquid metal flows into the preheated ceramic mold, filling every crevice the wax once occupied. This dramatic transformation from liquid to solid happens in minutes, yet determines the casting's structural integrity. Proper pouring technique prevents air pockets and ensures complete filling.

After cooling, the shell removal process begins. Workers carefully break away the ceramic mold with hammers and chisels, revealing the rough metal casting within. This stage requires controlled force - too aggressive and the metal may be damaged, too timid and the process becomes inefficient. The removed shell often shows fascinating details of the casting process, with metal having filled even the tiniest impressions. What emerges is a metal version of the original wax, complete with sprues and vents that must now be removed.

The cutting and cleaning phase transforms the raw casting into something resembling the final product. Using jeweler's saws, torches, and grinders, craftspeople remove sprues and excess metal. This stage reveals whether the casting was successful - internal voids or incomplete sections may require repairs or become scrap. For complex pieces, this can take longer than the initial wax work, as each cut must preserve the artwork's integrity. The piece begins taking its final form, though surface imperfections from the casting process remain.

Metal chasing follows, where artisans use specialized tools to refine details and repair any casting flaws. This handwork brings back definition that may have been lost during casting, recreating textures and sharpening edges. Chasers work under magnification for jewelry pieces, or with heavy tools for large sculptures. Their tools - punches, gravers, and repoussé hammers - become extensions of their hands as they perfect surfaces. This stage bridges the industrial casting process with fine artistry, requiring both technical skill and aesthetic judgment.

The assembly stage becomes necessary for multi-part castings. Complex designs often require separate casting of components later joined by welding, soldering, or mechanical fasteners. This phase tests the founder's planning, as pieces must fit perfectly despite metal shrinkage variables. For monumental sculptures, this might involve engineering substantial internal supports. The joining process must be invisible in the final product, maintaining the illusion of a single poured form. Proper assembly ensures structural integrity that will last generations.

Surface treatments through patination and finishing bring out the metal's visual qualities. Chemical patinas create colors ranging from bronze's verdigris to silver's black oxidation, while mechanical finishes produce textures from mirror polish to satin matte. These treatments protect the metal while achieving the desired aesthetic. Artists may layer multiple techniques, using abrasives, heat, or chemicals to create depth and contrast. This stage significantly impacts the piece's final appearance, transforming bright metal into something with character and presence.

The final polishing and buffing perfects the surface to jewel-like quality. Progressive abrasives remove microscopic imperfections, followed by polishing compounds that bring out the metal's luster. For wearable pieces, this ensures comfort against skin; for sculptures, it enhances light reflection. The polishing intensity varies by design intent - some pieces retain tool marks as evidence of handcraft, while others achieve flawless surfaces. This last step prepares the piece for presentation, whether in a gallery case or on a collector's body.

Lost-wax casting's enduring appeal lies in this marriage of predictability and artistry. While the process follows defined steps, each piece bears unique marks of its creation. Modern technology has introduced efficiencies, but the human element remains irreplaceable - from the sculptor's initial touch to the polisher's final stroke. The twelve transformations from wax to finished metal represent not just a manufacturing process, but a continuum of craftsmanship stretching back millennia. In an age of mass production, objects created through this painstaking method carry the weight of history and the imprint of individual hands.

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025

By /Jul 30, 2025